Gov. Bruce Rauner has little to say to journalists, and that's not just a problem for reporters.

Analysis: Within the steady din of turmoil that has characterized the first months of Donald Trump’s presidential administration, there was a moment recently that stood out, chillingly.

“FAKE NEWS media is not my enemy,” Trump tweeted on February 17, citing specifically the “failing” New York Times, CNN and others.

Instead, he declared, “It is the enemy of the American people!”

Even within the context of an administration that has gleefully broken one convention of modern American politics after another, this one was startling. As journalist Daniel Politi pointed out in Slate, the “enemy of the people” construct is, literally, the mantra of dictators — the phrase favored by both Josef Stalin of Soviet Russia and Mao Zedong of China to identify and eliminate dissent. Outrage over Trump’s comment crossed party lines. Republican U.S. Sen. John McCain warned in an NBC News interview: “When you look at history, the first thing that dictators do is shut down the press.” Eliot A. Cohen, the neoconservative former counselor in President George W. Bush’s state department, called it “the language of an aspiring tyrant.”

Beyond the shadow of potential dictatorship, though, the immediate challenge for journalists isn’t what the Trump administration is saying, but what it isn't saying. In some ways, the new president is merely upping the ante of his Democratic predecessor, Barack Obama, whose administration, too, was famously uncommunicative with working journalists. Trump has dressed up the silence with insults and threats, but at the core of it is still silence. It's a clear signal from a person put in power by the public that he doesn't believe he is obligated to answer questions from the public’s proxies in the media — questions members of the public can't realistically ask on their own.

It’s part of a growing attitude in the ruling class that didn’t start with Trump. And it isn't confined to Washington.

First-term Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner — a Republican who, like Trump, comes from the business world rather than politics — won office in 2014 after a campaign that veteran political reporter Carol Felsenthal told Columbia Journalism Review was “far and away the most closed organization I’ve encountered.” In one incident around that time that got national attention, the Rauner campaign allegedly responded to tough media coverage by pulling strings in the corporate brass of the Chicago Sun-Times to prompt the de facto demotion and ultimate resignation of a troublesome reporter.

In his two years since taking office, Rauner has continued to run what journalists say is a notably tight-lidded, inaccessible administration. “Even when he is physically present, he doesn’t answer questions,” says Charles N. Wheeler III, director of the Public Affairs Reporting program at the University of Illinois Springfield and a former long-time Statehouse reporter for the Sun-Times. “He seems to be more disciplined than, certainly, the governors I covered.” That discipline veered toward the comical in late February when, in the course of refusing to answer reporters’ questions on a budget proposal he’d unveiled a week earlier, Rauner was asked how old he’d turned during a recent birthday — and he initially refused to answer that question either. (“I’m 61,” he finally said, after getting the nod from his press spokesperson.)

The Trump-Rauner dynamic of dealing with the media — or rather, not dealing with them — isn’t just about the coincidental governing styles of two individual chief executives. There are troubling indications that it’s part of a wider movement among politicians trying to systematically delegitimize the traditional “watchdog” role of the press over executive power, using advances in social media and the fervor of populism to get themselves out from under that pesky scrutiny. All for the good of “the people,” of course.

In neighboring Missouri, for example, newly seated Republican Gov. Eric Greitens declined to release his tax returns during the campaign or since, didn't conduct his first open-ended news conference until almost two months into his term, and has presided over what Jefferson City journalists say is the most arm’s-length media relationship in memory. “It’s like covering a brick wall,” veteran Missouri political reporter Phill Brooks of KMOX radio recently told Gateway Journalism Review. In a move that almost looked like a deliberate message, Greitens’ administration had a coded lock installed on the entry to the governor’s press office so that reporters can no longer freely walk in when they want face time with the press staff.

Why should anyone who isn't a reporter care? Because Greitens holds policy power that has already turned Missouri into a “right-to-work” state, an epic change to the employment environment regardless of your view on the topic. And because Rauner is wrestling with a state budget crisis that has already necessitated shuttling of some services with worse potentially in store — not to mention the possibility of a tax hike. And because Trump, well, has nuclear weapons. Elected leaders by definition hold immense power over the lives of their constituents, most of whom have neither the specialized knowledge nor logistical capability to sit those leaders down and demand that they, as the late Chicago columnist Mike Royko once put it, “spell it out for us, nice and slow.” Pressing that demand is the reporter's job. And each time elected officials find new ways to avoid reporters, it's their own constituents who lose.

A common thread between the biographies of Trump, Rauner and Greitens is the fact that none of them had run for elective office before winning their current posts. Going into their respective elections, all three genuinely were what most politicians falsely claim to be: political outsiders. Perhaps it was their electoral inexperience that made them believe they could sidestep the traditional vetting that the media provides in campaigns and still win. And then it turned out they were right.

The lesson they apparently took from that is an ominous one for those who still believe that democracy can’t function without a vibrant and relevant press—especially at a time when the balance of power between journalists and the politicians they cover has shifted dramatically toward the latter.

“Until recently, the press relied on politicians for access to information while politicians relied on the press for access to the public’s ear. This ensured that government officials would never shut out the press entirely,” law professors RonNell Andersen Jones of the University of Utah and Sonja R. West of the University of Georgia wrote in The New York Times in January. “But with the fragmentation of the news industry, this is less true; the established news media can no longer claim to be the primary source of the public’s information.” They note that “when the president can convey his messages directly via Twitter, the press loses even more power.”

That shifting dynamic hasn't been lost on elected officials at all levels.

“Governor Rauner believes journalists are critical in ensuring that government is transparent and accountable to taxpayers,” Rauner’s office said in an emailed statement to Illinois Issues — but added, “As technology and media diversify, he also continues to look for new and innovative ways to communicate with his constituents.”

Responding to the question of access, Rauner's office issued a count of almost 370 public events he conducted in 2016 alone that allowed journalists to question him, including individual interviews, press “gaggles” with multiple reporters, newspaper editorial board meetings and radio call-in shows. That count didn't differentiate whether, as in the February post-budget media gaggle, he declined to substantively answer reporters' questions.

Access is Tightening

Although many today talk about potential First Amendment threats, what exactly could a president (or governor) who is hostile toward the free press in 2017 America do about it? Are we talking about armed government forces showing up in the lobby of The New York Times or the Chicago Tribune and literally, physically halting production of the newspapers and their affiliated websites?

That's unlikely. Yes, as McCain points out, ascendant dictatorships historically shut down the media first. But how many of those ascendant dictatorships had a 240-year tradition of free speech and press at the core of its founding document, its institutions and society itself? As much as things seem to have changed lately, we still have the most ubiquitous, culturally embedded media in the history of civilization — more so now than ever, in fact. Whatever dangers the free press might yet face, the specter of armed soldiers marching into an American news room still seems remote.

But if that nightmare scenario isn't a realistic danger, another one seems very real and currently in play. To prevent reporters from doing their jobs via lack of access can be as effective as doing it via force. And from D.C. to state capitals, access is tightening.

With the Trump White House it has often been brazen, as when, on February 24, White House spokesman Sean Spicer blocked The New York Times and other serious outlets from a briefing on the heels of some hard-hitting coverage, while allowing in such sycophantic pretenders as Breitbart.

In Missouri, Greitens has mostly eschewed live announcements and traditional news conferences in favor of, for example, a recent Facebook video event in which he took questions directly from the public. The administration touted it as a new level of transparency; in fact, it was the opposite because the questions were prescreened. That may explain why Greitens didn't answer questions some in labor (and the media) are asking about how his right-to-work legislation will affect prevailing wages in Missouri, a real issue affecting his own constituents — but found time to riff on the question of, “Why does the media bash you so much?”

With Rauner, reporters say, it’s been more subtle issues, like public appearances that aren’t declared off-limits for media questions but effectively turn out to be; or a lack of back-and-forth discussion with reporters about this year’s budget proposal, a key issue in a state under perpetual budget crisis these days — an issue that, one way or another, ultimately affects the lives of virtually every resident of the state.

Some say Rauner’s general inaccessibility to the press is less a sharp turn than an evolution that has been in progress during the past several gubernatorial administrations. Rich Miller of Capitol Fax, who has covered every governor since Jim Thompson, recalls an aide to George Ryan — shortly before his election as governor almost two decades ago — threatening Miller over his coverage by declaring that, once elected, the new administration was “going to call all the lobbyists and cancel all your subscriptions.”

“Would I like [Rauner] to be more open? Yeah,” says Miller, citing as an example how Rauner “doesn’t tell people when he goes on vacation or where he’s going.” He added, though: “It’s a trend. . . . I've been cut out by governors before, and I don’t feel like I’ve been cut out more by this one.”

Several other Statehouse reporters were understandably hesitant to talk on the record about Rauner’s relationship with the media, for fear of worsening it. The general consensus is that it’s bad, but that it's been bad for the past few administrations. The dark ages of Ryan and Gov. Rod Blagojevich in particular are commonly referenced (though perhaps those aren't the best comparisons, given that both men spent much of their tenures skidding toward indictment). One journalist blamed in part the advent of email, a double-edge sword that makes it easier for reporters to ask questions of governors’ staffs — but also makes it easier for those staffs to sidestep questions by sending non-answer answers without being subjected to face-to-face interaction.

Wheeler, the veteran journalist now with the Public Affairs Reporting program, notes that social media in general has made it easier for politicians to get around journalistic scrutiny. “When I was a reporter there was no social media. Politicians had to rely on us to get their message out. Nowadays, they tweet, they use Facebook, and they're able to circumvent the press.”

To anti-media critics who would respond to that notion with a victorious fist pump, consider: What motive might politicians have for not wanting to be questioned by the people whose very job is to prevent politicians from lying to you? “If I’m a salesman and I’m trying to sell my product, and I can present my product in glowing terms with no downside,” notes Wheeler, “of course I'm going to do that.”

`Some of Trump in Walker'

While there's little doubt that doors of power have been getting increasingly slammed against journalists at all levels of government lately, it's important to remember that press access trends have historically been cyclical. To some extent, we've been here before.

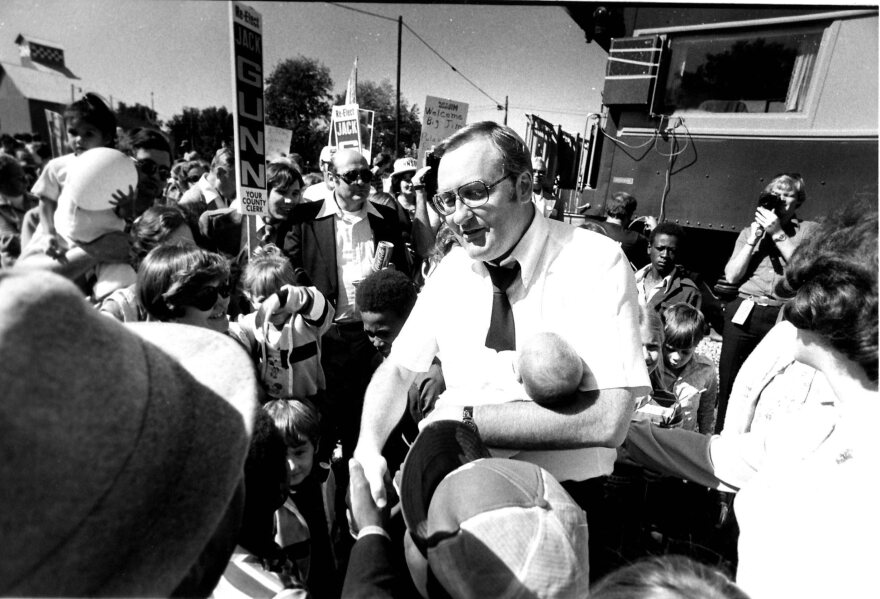

Taylor Pensoneau, who covered the Illinois Statehouse for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch from 1965 through 1978, has seen what open access for journalists looks like. Gov. Sam Shapiro was “amiable” with reporters during his eight-month tenure; Gov. Richard Ogilvie “genuinely liked us.” Lt. Gov. Paul Simon, a former newspaper man himself, was “one of us.” During Thompson's administration, “It would not be unusual to walk in and see Thompson lying on the couch in the Sun-Times cubicle in jeans and a golf shirt with a beer in his hand,” recalles Pensoneau.

But there was also Gov. Dan Walker, the outsider-populist one-term Democrat of the mid-1970s, whose approach to media relations should sound familiar to anyone watching our new president.

“Walker had a terrible relationship with the Statehouse press corp,” recalls Pensoneau. “He was anti-establishment — to use the modern phrase, he ran to ‘drain the swamp’ in Springfield — and he felt that most reporters in the Statehouse were in the pockets of the establishment. He intentionally engineered a hostile relationship.”

In that pre-social-media era, Walker would look for other ways to circumvent Statehouse reporters, Pensoneau said, such as releasing his budgets at far-flung town meetings instead of in the Statehouse, so that the only journalists on hand to grill him about it would be local reporters with no background on the subject. “He was not readily accessible to most reporters” in Springfield, Pensoneau says. “As part of [the administration’s] political approach, they had to be at odds with the Illinois press corps.”

Pensoneau eventually cultivated more rapport with Walker and ultimately became his biographer. He said Walker expressed regret later in life about his strategy of making the press his foil. “He was very confrontational — he thought that was part of his mystique. He would institute confrontations that had nothing to do with governing Illinois. . . . There was some of Trump in Walker.”

Trump is by no means the only modern incarnation of the Walker approach to media relations.

When former Illinois Statehouse reporter Kurt Erickson, now covering the Missouri Statehouse for the Post-Dispatch, reported in February on the Greitens administration’s systemic shutout of media access, Greitens' office promoted the story as if it was a compliment. “@EricGreitens communicates directly with the people (& answers their questions) — no filter from liberal media,” crowed Greitens spokesman Austin Chambers in a tweet linking to Erickson's story. (For the record, issues on which Greitens has pointedly not answered questions — from reporters, “the people” or anyone else — Include the source of a record $1.9 million donation his campaign received last year; his connections to a nationally known “dark money” consultant; and his own tax returns).

Loudly vilifying reporters to create a foil isn’t Rauner’s style; he's more like the CEO who has security discreetly block them from the board room. But whatever the methodology, politicians who stiff-arm the press today may feel emboldened to do that — stiff-arming the public in the process — because of signals out there that the public will let them get away with it.

A Pew Research Center poll released March 2 found that just 64 percent of Americans agree it’s “very important” to democracy that “news organizations are free to criticize political leaders.” Among Republicans, the number is 49 percent — which means that a majority of members of the party that currently holds the preponderance of political power in America doesn’t believe it's all that urgent to keep political leaders in check with a vibrant press.

Kevin McDermott is a political reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Illinois Issues is in-depth reporting and analysis that takes you beyond the headlines to provide a deeper understanding of our state. Illinois Issues is produced by NPR Illinois in Springfield.