Analysis: What should be done to respond to loss of rural population?

Stark County in central Illinois has lost population every decade since 1880 and now counts fewer than 6,000 residents, half that of the late 19th Century, notes Jim Nowlan, editor of Stark County News. Like Stark, rural counties throughout Illinois, lag behind metro areas on key economic indicators such as employment changes, income and population. The trends, which are mirrored in other states’ rural reaches, may have worsened since the Great Recession.

Declining birth rates and aging-in-place also have implications in terms of the fiscal stability of local governments and ability to provide essential services to aging residents. Likewise, finding younger workers to replace retirees will be necessary to maintaining a quality of life that retains current residents, as well as attracts newcomers. The result is an older population which, combined with the departure of young residents and those of working age, could lead to serious work force issues and eroding their economic vitality, as well as limit their ability to attract businesses and quality jobs.

Many rural Illinois counties have declined in population relative to their metro counterparts for many years, with 45 rural counties in Illinois having a smaller population in 2016 than they did in 1950. A main cause has been the continued mechanization of agriculture that dramatically reduced employment in this industry, which directly affected rural communities that relied on these producers as customers. Advances in internet sales are now threatening local retail sales which could also reduce employment.

Although manufacturing still has a strong influence on the rural Illinois economy (manufacturing represented approximately 10.9 percent of total employment in 2016 compared with an average of 7.8 percent statewide), some industries are relatively labor-intensive and have been adversely affected by automation and off-shore competition. Job losses in these industries have meant further declines and shrinking markets for other rural businesses.

The increasing proportion of young people pursuing higher education has also led many to leave, or not return to, rural communities. In addition to relatively fewer employment opportunities for those with four-year degrees, the growing wage differential between rural and metro areas encouraged graduates to seek higher-paying jobs in expanding metro areas.

While there is growing evidence that after starting a family, they may prefer more suburban locations, there is little evidence to suggest they will return to rural areas partly because many of the jobs do not pay an acceptable salary for graduates from higher education.

These broad demographic trends mean that in the future, older populations will be replaced by Millennials (21-35 years) who are fewer in number and have marked a preference for living in larger urban areas partly because of lifestyle preferences. However, there is some evidence of a return by older Millennials (35-44 year olds) in a trend that has been called a “brain gain.” Thus, in some counties, a population decline in a county may hide outmigration by early Millennials but a return by those in their 30s.

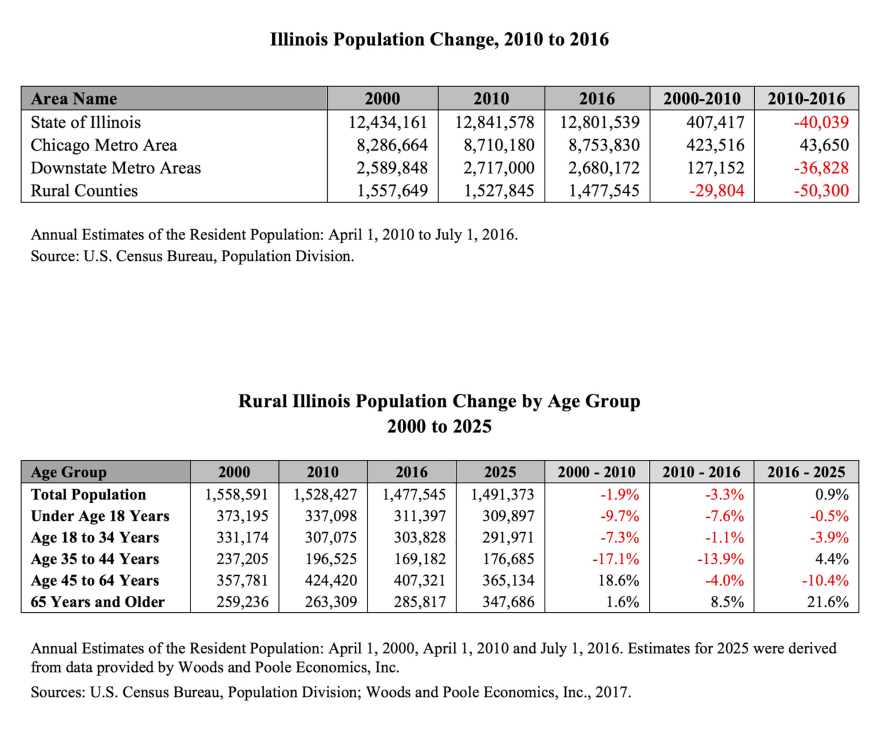

Between 2010 and 2016, the state of Illinois suffered a net loss of approximately 40,000 residents or 0.3 percent of its 2010 population. Gains in the Chicago metropolitan area were not enough to offset substantial losses in downstate metropolitan areas but especially in the rural counties. These counties suffered proportionally higher losses (3.3 percent) than the downstate metropolitan counties (1.4 percent) and continued a downward trend where Illinois rural counties had a net loss of nearly 30,000 residents between 2000 and 2010 even though metropolitan areas gained population.

The source of recent population declines is primarily the result of the exits of residents rather that to natural decreases (i.e. ratio of births to deaths), according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In the rural counties, net migration accounted for approximately 85 percent of the population loss between 2010 and 2016. In the metro areas, a higher number of births over deaths offset at least partially population losses stemming from outmigration.

Some rural counties in southern and western Illinois are remote, depend heavily on agriculture or mining, and lack easy access to large employment centers. Some areas such as southern Illinois, with large parks and recreational areas such as the Shawnee National Forest, tourism is also an important part of the economy. Coal mining was a major employer but has declined in recent years because of regulatory changes. Western Illinois depends heavily on agriculture and lacked a modern highway system until the past decade or two.

The consquences are real. For instance, Christopher Merrett, director of the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs at Western Illinois University, says, “Many small towns have lost pharmacies forcing residents to travel to larger towns to refill prescriptions. While there, they also make other purchases, meaning lost business in their smaller home town.

“Some communities partner with private agencies to maintain brick and mortar retail in an era of increasing online sales and competition from big box merchants,’’ Merrett says. “Tele-pharmacies provide a partial solution to this challenge by using broadband and videoconferencing technology to maintain pharmacies in small towns. Pharmacy technicians staff these tele-pharmacies and are connected in real time to licensed pharmacists in larger centers. For example, Abingdon [in western] Illinois, just opened up a tele-pharmacy inside an existing grocery store."

What does the future hold?

Past trends are likely to continue during the next decade or so. The 65 years and older population group will have the highest growth and will be a dominant factor in determining needs for housing and public services such as education and health care. This age group will also affect types of private goods and services sold in the rural areas because they will control a major part of the purchasing power.

Also important is that many local business owners and service providers are in the Baby Boom generation so rural communities will have a substantial number of business closings unless young adults are willing and able to purchase and operate them. Business succession planning, then, will be especially important to retain wealth in rural areas as well as stabilize businesses and services required for a high quality of life to attract other residents.

The 18 to 34-year age group is also expected to decrease 3.9 percent in rural counties by 2025. But, as already mentioned, this includes two groups — those who leave rural areas to pursue higher education or work opportunities and others who, under the right opportunities, migrate back to rural areas. So, family ties can be important but high quality living environment with public services and job opportunities that meet their interests are equally influential in location decisions.

Past and projected population trends for rural counties in Illinois have several important policy implications and other states can show examples of how they are addressing these issues. Above all, the business climate in rural areas must be competitive with both metro areas and other states to attract and retain quality jobs. Property and income taxes, Worker’s Compensation rates, and other business-related issues always come up in discussions. Uncertainty about the states’ fiscal matters has also been a major issue in recent years and is likely to continue.

Other important issues arising from continued outmigration including changes in numbers of school age children in the next 10 years or so. Statewide, those under 18 years of age are expected to increase 2.5 percent between 2016 and 2025, but are expected to decline half a percebt in the rural counties. The trends are equally concerning for the younger working age people (age 18 to 24 years old) which is projected to decrease 3.6 percent statewide and 9.1 percent in rural counties. These trends will affect K-12 school systems, as well as post-secondary institutions.

Equally important are the possible impacts on the work force in rural areas. While the expected gain (2016 to 2025) of 4.4 percent in the 35-44 year cohorts is encouraging, it does not compensate for the projected loss of 10.4 percent in the 45 to 64 year groups. This means that the overall working age population in rural counties will probably decline by 2025 even without considering the impact of continued outmigration. Compounding this issue is that labor force participation has declined in rural counties from 60 percent in 2010 to 57.5 percent in 2016, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

While the Illinois trends are not necessarily unrepresentative of rural areas in other states, they do point to a need for additional efforts to not only increase the number of young adults who participate in apprenticeships but also explore ways to retain experienced workers in the labor force after they have reached traditional retirement age. Illinois is making strong efforts to increase apprenticeship opportunities and provide pathways for graduating students to reach the job market better prepared.

However, there may be opportunities to provide incentives to retain experienced workers in the labor force.

Companies already use flexible hours, part-time employment status, bonuses, restructured work environments and other approaches to retain employees, especially those with experience and current skills needed in operations. To retain workers who qualify for retirement benefits in rural areas, however, means that the quality of life must suit them which may mean additional health care and other services. Population projections suggest that more of these and similar efforts will be needed in the future.

The fact that a significant proportion of the population declines in rural Illinois result from outmigration rather than natural causes may offer opportunities for state policy adjustments to promote the business climate in downstate Illinois, create quality jobs, and ultimately retain more population including young adults. Some states such as Wisconsin have initiated programs such as low cost housing loans aimed at attracting young families. Other states such as Washington have programs to encourage collaborative investment in technology advances in rural areas.

In some places, the business-backed Creating Entrepreneurial Opportunities (CEO) program has succeeded in stimulating interest among secondary school students in starting local businesses. When local financing is available, there is a serious opportunity for rural areas to launch successful ventures. Linking these efforts to an organized business succession planning effort could help stem the losses of businesses because of owner retirements and might help slow the outmigration of young adults as well as maintain the quality of life in the community.

In Stark County, Nowlan, the newspaper editor, says, “A few local leaders would like to build Stark County into the ‘Specialty Crop Capital of the Midwest,’ just as the southern part of Chicago’s Cook County was a century ago. If we could establish a critical mass of, say, 100 specialty growers, each on about 15 acres (a total of only 1 percent of the county’s farmland), we could truck produce daily to the 11-million population three-state Chicagoland market, where consumers cry out for fresh produce. And with hoop houses, we can grow produce 11 months a year.”

Statewide, the DCEO Regional Economic Development (RED) team works with local officials and community leaders to stimulate the local economy building on industrial strengths. This approach provides an opportunity for rural regions to design strategies and policies that build on local assets and capacities to grow the local economy.

The Governor’s Rural Affairs Council, (GRAC) operating since 1987, monitors rural conditions and offers recommendations for policies. This council, chaired Lt. Gov. Evelyn Sanguinetti, coordinates efforts of state agencies that serve rural areas so has an opportunity to work with relevant state organizations to update or design an overall rural development action plan that enhances rural areas by increasing jobs and helping to stem the outmigration.

Rural Illinois is undergoing a transition not unlike many other states with an aging population, outmigration of young adults, and possible shrinkages in future work forces. Some of these issues can be addressed through an organized public policy approach designed to address specific issues. Illinois has opportunities through DCEO, GRAC, and other agencies to design an effective strategy(ies) for rural counties to help stem the outmigration, help stabilize the population, and improve their future prospects. A coordinated effort(s) could offset some adverse expected population trends.

Norman Walzer and Brian Harger , respectively, are senior research scholar and research associate in the Center for Governmental Studies at Northern Illinois University.

Illinois Issues is reporting and analysis taking you beyond the daily news and providing a deeper understanding of our state.

As someone who values being knowledgeable about Illinois, please support this public radio station by clicking on the, "Donate," button at the top of this page. If you're already a supporter, thank you!