When John Beetz’s great-great-grandfather came to America from Germany in the mid-1800s, he worked as a longshoreman in New York. Then he turned to farming the fertile soil in north central Illinois.

Succeeding generations built on their ancestor’s legacy. And today, Beetz and other members of his extended family farm 8,000 acres near Mendota in LaSalle County. In fact, they operate one of the largest farms in the state. Yet they remain dependent on federal farm subsidies.

“If there were no subsidies, I would not be able to pay my expenses and I’d have to quit farming,” says the 53-year-old Beetz, whose family partnership received $1.5 million in federal farm aid between 1996 and 2000.

His predicament illustrates the difficulty lawmakers face as they try to rework the 1996 farm law. The House already has endorsed a plan to increase traditional crop subsidies. The Senate is likely to back a different approach, one that shifts dollars to programs aimed at encouraging conservation practices on farmland. But in this debate, the issue isn’t whether to offer farmers an income safety net, but which farmers, how much and for what reasons.

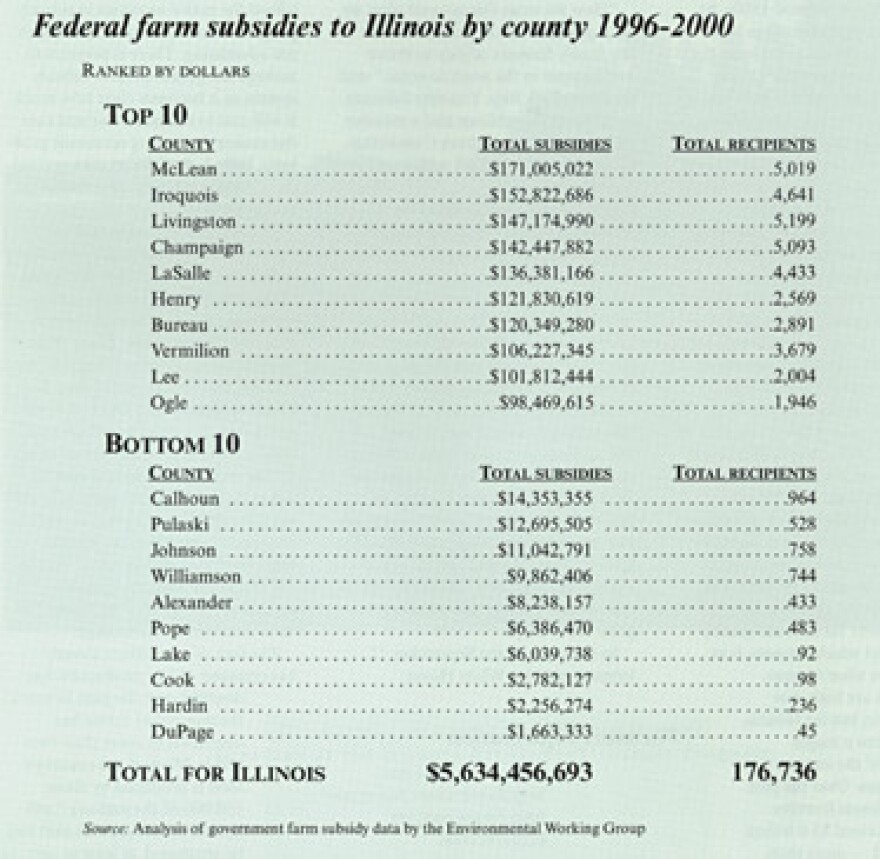

The stakes are high, not only for Beetz, but for Illinois, which has been a major beneficiary of the current subsidy system. Over the past five years, Illinois farmers statewide received $5.6 billion in federal aid — more than farmers in any other state except Iowa and Texas.

“How we write this act and what we do is going to set the parameters for the family farmers’ ability to thrive and prosper in the years to come,” said freshman U.S. Rep. Timothy Johnson, an Urbana Republican and a member of the House Agriculture Committee, as the debate kicked off with that panel in July.

Illinois and other states in the Midwest and the South have histor-ically benefited from support systems that favor such crops as corn, wheat, rice and cotton. And many Illinois farmers and ag groups would like to keep it that way. However, lawmakers from New England and the Western states, which haven’t benefited from subsidies, are turning to farm conservation programs as a way to steer money their direction. Their cause was strengthened when President George W. Bush’s administration called in September for a shift toward programs that promote environmentally friendly farming practices and international trade and away from subsidy programs that reward a few large operators who grow select crops.

In the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks, White House officials also expressed concern over whether the federal government can afford the major increases in subsidy programs that farm-state lawmakers are advocating. There is pressure to reshape the generous farm subsidy system as it becomes clear how much it will cost to finance a war and ease the country’s growing economic problems. Even before the attacks, revised fiscal forecasts predicted a dwindling budget surplus.

Though it wasn’t supposed to, current federal farm policy has proved to be expensive. The GOP-authored “Freedom to Farm” law enacted in 1996 was designed to wean farmers off federal subsidies, while giving them more control over what they can plant. Instead, crop prices plummeted and Congress approved a series of emergency bailouts, spending almost $30 billion more than originally planned.

“Farmers aren’t happy about depending on the government for their net income, I can tell you,” says Joe Hampton, who heads the Illinois Department of Agriculture. “But in the absence of that, the face of agriculture would change; the face of rural America would change.”

The face of agriculture already has changed. While production has doubled over the past 50 years, the number of farms has decreased by more than two-thirds. Most of the country’s food is produced by about 150,000 of the nation’s 2 million farmers. And this shift can be attributed, at least in part, to government policies. The farm subsidy system has created “unintended consequences” by encouraging overproduction and driving up land prices, concludes a 120-page report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“Highly efficient commercial farms benefit enormously from price supports, enabling them to expand their operations and lower costs even more,” the report says. “Other farms have not received enough benefits to remain viable and have been absorbed along the way.”

Farm program benefits go to just 40 percent of farms nationwide. Almost half of the federal money goes to the nation’s largest farms with an average household income of $135,000 a year. In Illinois, 10 percent of farm aid recipients collected 60 percent of the funds in the past five years, according to a recent analysis of government farm subsidy data by the Environmental Working Group. Even nonfarmers can harvest crop subsidies if they hold title to the land. That’s how media mogul Ted Turner, basketball player Scottie Pippen, the University of Illinois and Caterpillar Inc. make the recipients list.

“The programs are always justified as saving the family farm and providing food security, and that’s just not the way it plays out,” says Environmental Working Group President Ken Cook, who is lobbying for more conservation spending, including support for farmers who provide habitats for wildlife or protect wetlands. Currently, most conservation funds are paid to farmers to idle land, a strategy that aims to protect soil and water resources.

Many environmentalists and a growing number of lawmakers, including those in urban and suburban areas, say a greater emphasis on conservation funding would be a fairer way of distributing federal assistance. It could help farmers with small operations and those who grow such crops as fruits and vegetables that don’t currently qualify for subsidies. And taxpayers, they contend, would enjoy a greater return on their dollar through environmental improvements that would benefit everyone.

Further, conservation spending might be less likely to run afoul of international trade agreements the United States has signed to reduce farm subsidies, administration officials and others have said.

Angering farm-state lawmakers, the White House came out against a $170 billion, 10-year farm bill just as the House began debate on the measure in early October. The administration argued the bill is too costly given the nation’s economic problems and security concerns.

It also contended the measure’s continued reliance on subsidies encourages overproduction when prices are low and it fails to help the farmers who need it most.

In open defiance, Republican House leaders ignored the president’s request to delay action on the bill. House members, in a key vote, narrowly defeated an effort to shift billions of dollars from crop subsidies to conservation programs over the next decade. The amendment by Reps. Sherwood Boehlert, a New York Republican, and Ron Kind, a Wisconsin Democrat, was supported by a coalition of environmental, recreation and sportsmen’s groups.

It also had the endorsement of the National League of Cities and the American Water Works Association.

But all of the major farm groups lobbied vigorously against the amendment, which would have redirected $19 billion over 10 years to environmental programs. “They’re intending to rip money away from the heartland and give it to either one of the coasts,” said Bruce Knight of the National Corn Growers Association as the debate opened. “Clearly, Illinois farmers are losing out with this proposal.”

Hampton argued that “farmers have to be in business in order to participate in conservation programs. The conservation programs themselves aren’t going to provide a livelihood.”

The amendment’s supporters acknowledged Illinois funding would be reduced slightly under their proposal, but said it would affect only the largest producers, leaving 97 percent of farmers unaffected. Of Illinois’ House members, only a handful from the Chicago area supported the amendment. Rep. Lane Evans, whose west central Illinois congressional district collects more farm subsidies than all but one other district in the state, initially said he would support the amendment because it would aid more small farmers. But the Rock Island Democrat, who says his farm constituency will grow after redistricting, changed his mind on the day of the vote when he saw a new analysis of severe cuts to farmers in his district.

Rep. Ray LaHood, a Peoria Republican, argued against the amendment, though his district has benefited from conservation programs, the largest of which pays farmers not to plant on environmentally sensitive lands along the Illinois River.

The House went on to easily approve the overall bill, which would boost current program spending by $73 billion over 10 years. That measure would retain two existing subsidy programs and create a third “countercyclical” program to pay farmers when prices fall too low. It includes a $49 billion increase for commodity programs and a $16 billion increase for conservation.

If the bill were to become law this year, it would increase the average net 2001 income on an Illinois farm by $16,000, according to an analysis by University of Illinois agriculture economics professor Gary Schnitkey.

Both sides claim the close vote on the conservation issue gives them momentum as the focus now shifts to the Senate. The Senate Agriculture Committee was expected to start drafting its bill in late October.

Committee Chairman Tom Harkin, an Iowa Democrat, and Indiana Sen. Dick Lugar, the committee’s senior Republican, want to increase spending on conservation programs, advocating new ones to help farmers without taking their farms out of production. However, they differ greatly on overall spending.

Lugar on October 17 proposed limiting new farm spending to $25 billion over five years, phasing out crop subsidies by 2006. The Bush Administration endorsed the concept. Instead of subsidies, farmers would receive an annual voucher of up to 6 percent of their average gross farm revenue if they agree to certain conservation measures and buy insurance to protect them against revenue losses. All crop and livestock producers would be eligible.

The White House position “will clearly complicate the task of writing the new farm bill,” says Harkin, who supports the $73 billion increase over 10 years allowed under the congressional budget resolution, the amount approved by the House. Harkin has said he favors significant changes to the subsidy program to ensure the new farm bill is fair and “does not focus so heavily on the large cash payments to the biggest operations.” But his task will be difficult. The committee is dominated by farm-state lawmakers, and Harkin’s own state is the biggest beneficiary of current farm programs.

While Harkin is being pushed by Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle, a South Dakota Democrat, to finish work on the farm bill this year, U.S. Agriculture Secretary Ann Veneman maintains that it is “unnecessary and unwise to undertake action on a farm bill in this wartime, national emergency environment.” The current farm bill doesn’t expire until next September.

Any proposed changes concern Illinois farmers. On September 11, residents of Beetz’s small town ran to the gas stations to fill up their tanks, he notes. They didn’t rush to the grocery stores to stock up on food.

Maintaining a reliable food supply is, to him and many farmers, what federal farm subsidies are all about. “No senator in his right mind is going to let the country run out of food,” he says.

Background

United States

Department of Agriculture

http://www.usda.gov/

U.S. House Committee

on Agriculture

http://agriculture.house.gov/

Environmental

Working Group

http://www.ewg.org/

American Farm Bureau

http://fb.com

Dori Meinert is a Washington correspondent for Copley News Service.

Illinois Issues, November 2001